One type of article I’ve wanted to do again is surveying my fellow developers on a topic and compiling the answers. There’s a lot of insight to be gained from reaching out to others who’ve worked in different environments and have different outlooks on life and I don’t want to only share my own views here for these types of articles.

Last November I created & released a survey aimed at people who had led game jam teams for making visual novels. It’s a hard skill to grow, as leading other people and finishing a game in a set amount of time is a very particular skillset. So, I wanted to ask other creators about their advice to people who take on this endeavor. Some of these responses were left anonymously while others provided their contact information.

I was able to get feedback from 34 other visual novel developers, so let’s look at what they had to say!

stats

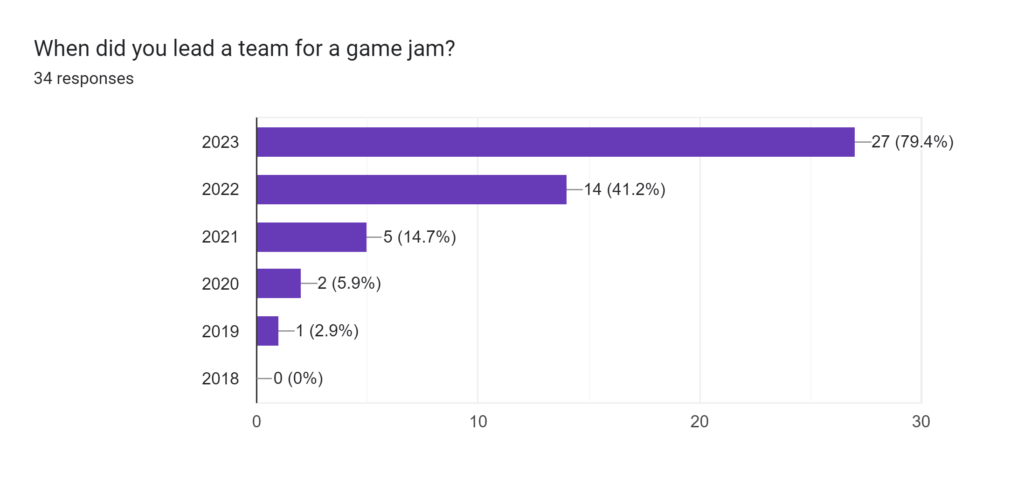

First off, let’s start with some general statistics about the people who responded.

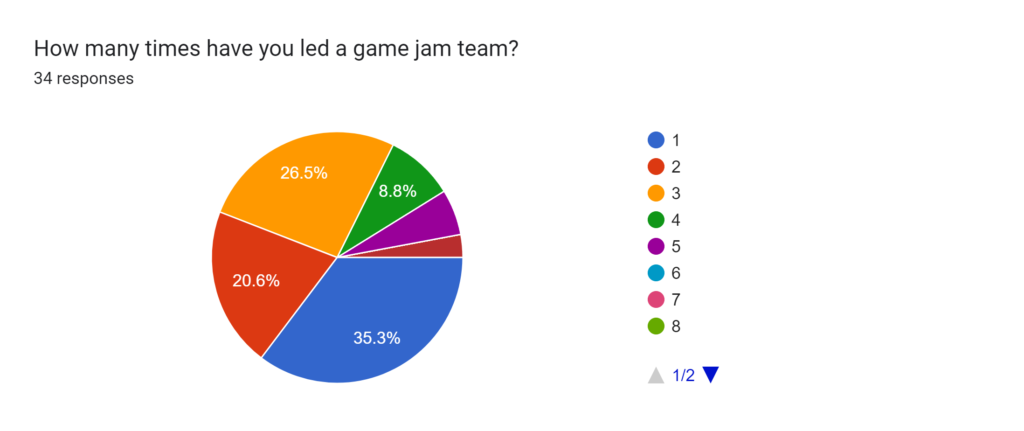

A majority of people are new-ish leaders who’ve led a couple of teams in the last year or two. However, almost half of them have led at least 3 teams, and 1 person led 9 jam teams! Personally I’ve led 3 teams for NaNoRenO, the annual visual novel jam in March.

Amount of jam teams led:

1 (35.3%)

2 (20.6%)

3 (26.5%)

4 (8.8%)

5 (5.9%)

6, 7, 8, 10+ (0%)

9 (2.9%)

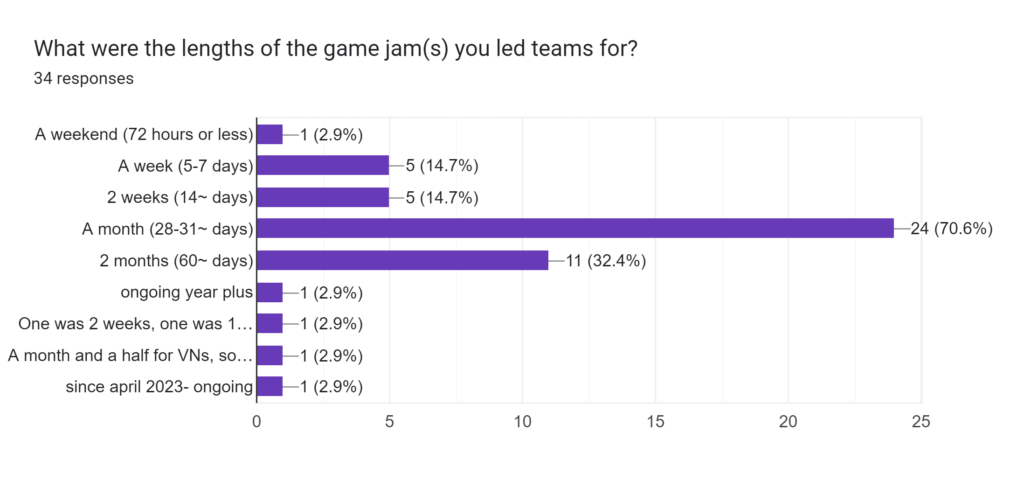

We can see that a majority of leaders were in a month-long game jam, as the largest visual novel jams are all around 1-2 months, like NaNoRenO, Spooktober, Winter VN Jam, and more.

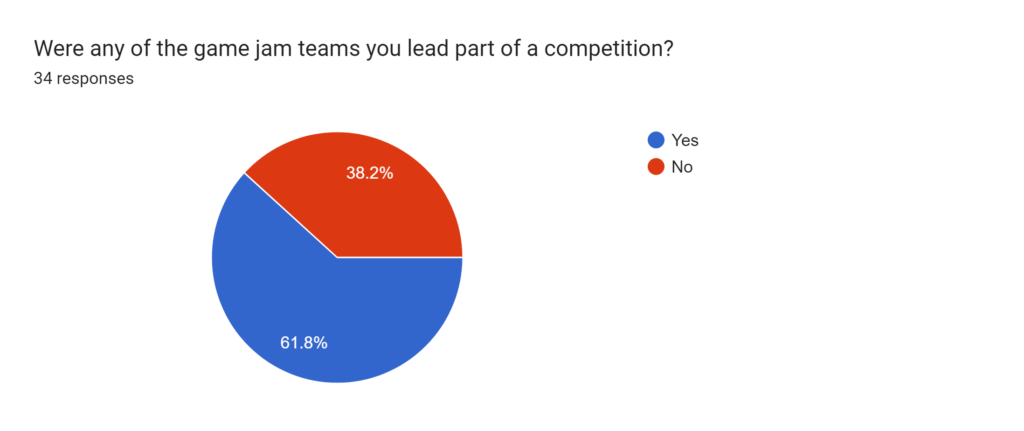

I also wanted to see how many of these game jams were competitions. I posted this survey right after Spooktober wrapped up, one of the largest visual novel jams that is a competition, so I’m not surprised a lot of the respondents had entered competitive game jams.

further details

Now that we’ve looked at some overall statistics, let’s dive a bit deeper into the team structures and set up.

How did you prepare your project before the game jam started?

Research the game jam and its rules, see if I can make concepts and outlines, create said early concepts to get them down, see if any acquaintances show interest in the project and from there see what other positions are needed and where I can [use Creative Commons] materials to substitute what I can’t do myself.

anonymous

We began brainstorming ideas 5 days in advance. I set up a Google Drive folder and a GitHub repository for sharing assets. I also planned out a timeline that we would stick to: 3 weeks to make the game, and the final week to add polish and fix any issues. The timeline also included weekly check-in calls to make sure the team was on track. But the team constantly shared updates with each other via Discord every day, too.

Kinjo Goldbar

Me and my teammates brainstormed a lot of ideas using word docs and Pinterest boards. From there, we created a brief story idea and began scheduling documents to track how long we would work on each proposed part for.

anonymous

I wrote the entire detailed outline with scene direction notes and used it to inform my asset sourcing: I made a Pinterest moodboard and started photobashing background references, I got all my free for commercial use sound effects, music tracks, fonts, and GUI packs; I conceptualized the character art (as I was also the character artist), and I planned a schedule with soft/preferred deadlines and hard deadlines for flexibility. Then I recruited team members with all this preparatory info on hand.

anonymous

I created a pitch for my project: featuring my planned scope and my inspirations for said project. I wanted to be confident about the game I’d work on before I worked on it. That way, I wouldn’t use precious jam time on sketches and other pre-preparatory work. After I was satisfied with my pitch, I recruited my required team members via public sign-up forms. Once they were picked, I gathered them all together in my game jam Discord server.

madocallie

Got a sense of each member’s skill set and tried to clearly define roles and how each would contribute to the team. I’d brainstorm with the other members and try to get a sense of how they want to approach the game jam, what video games they’re inspired by, etc.

anonymous

For myself, I would start pitching ideas with my friend(s) who agreed to help out and begin setting up recruitment forms. I wouldn’t recruit anyone until I had a document going over the basics of the project (genres, estimated length, aesthetics, etc.) and team member requirements (what was expected from each role). A lot of the larger visual novel jams have recruitment sessions before the jam starts that you can attend to find team members.

What was your main channel for communicating with team members?

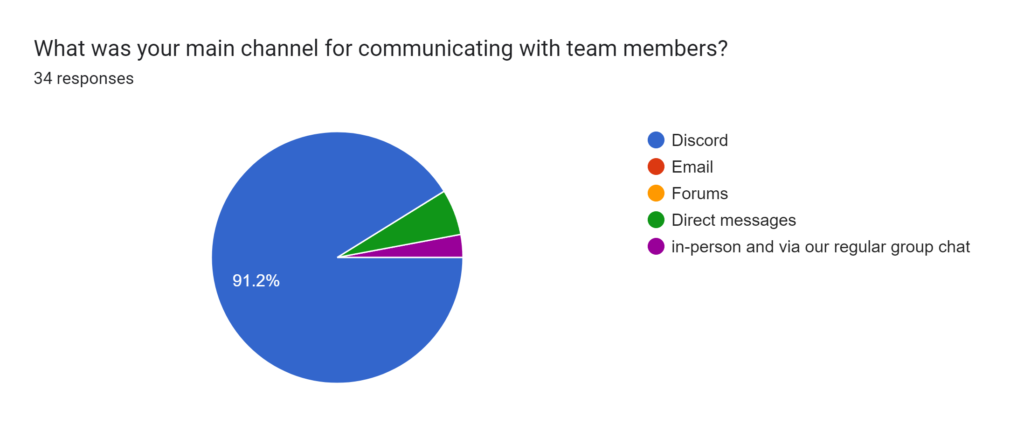

A vast majority of leaders communicated with their teams via Discord. Side note- I forgot in-person jams are coming back into fashion and forgot to include that here, as 1 person added an extra option to say they met in-person for their jam.

How often did you check up on your team members?

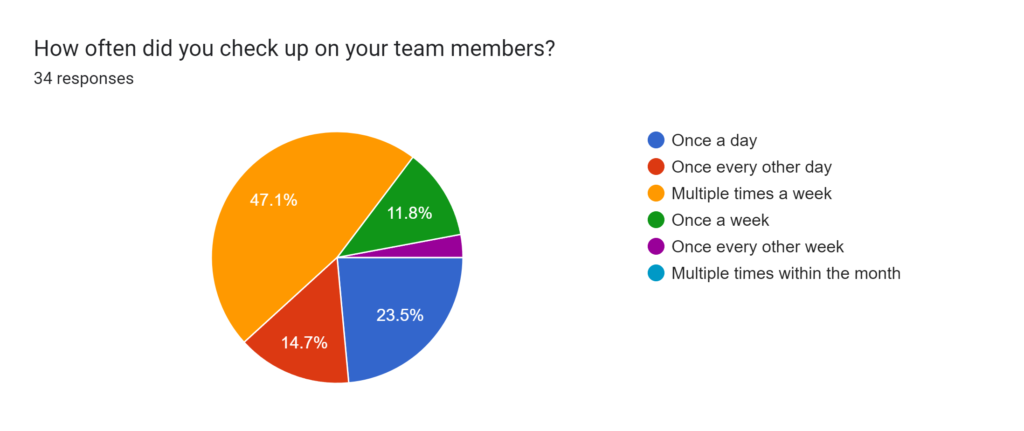

Most people checked in with their team members at least multiple times a week during a jam.

Once a day (23.5%)

Once every other day (14.7%)

Multiple times a week (47.1%)

Once a week (11.8%)

Once every other week (2.9%)

Multiple times within the month (0%)

What was the initial scope of the game?

For those unaware, scope is the entirety of a project, including the writing, art assets, music, characters, and more. I asked this question (and forgot to word it as “game(s)”) to give an idea of what people aim for in game jams. Not every user answered this question and some were counted twice because of their multiple projects.

Some scope estimations provided were:

Less than 10k (7 people)

10k words (9 people)

20k words (3 people)

30k words (2 people)

50k words (2 people)

Several people mentioned multiple endings, multiple routes, only one ending, partial voice acting, full voice acting, a handful of CGs, a lot of CGs, and more. All of this is to say that your visual novel can be any scope size you want. It’s your story and it’s okay to make it short or long.

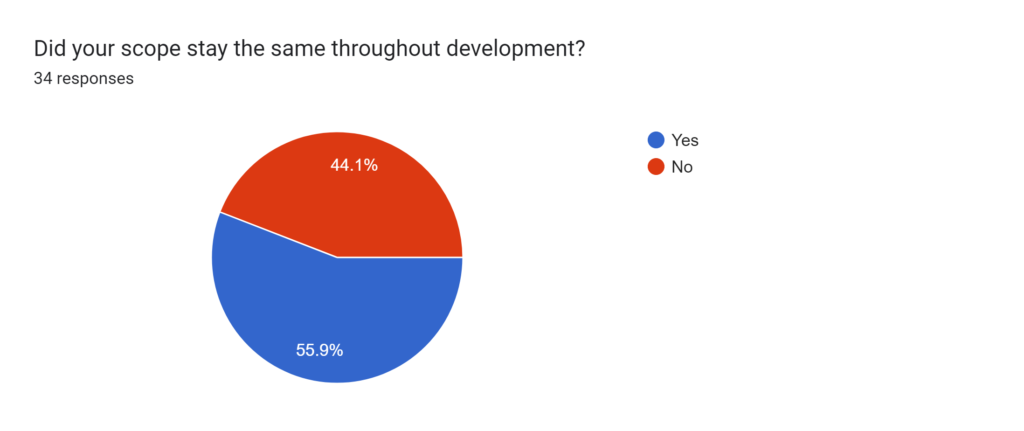

Did your scope stay the same throughout development?

While a majority of people said that their scope size stayed the same throughout development, it’s still a very close split with 19 people saying yes and 15 saying no.

It can be pretty hard to manage scope and keep it under wraps, especially for new developers. If you’ve never tackled scope management or finishing a game to completion, I encourage you to work on something on your own first or work as part of someone else’s team.

What was an unexpected issue you ran into during the project?

sound implementation – didn’t realise how frustrating it would be wrangling all of the volumes together in cohesion, as well as the degree of effort it takes for voice implementation.

rosesrot

There was scope creep with number and complexity of bgs, and a bunch of programming hurdles.

anonymous

The required scope encouraged creativity but was also very limiting, and a misunderstanding of the jam rules meant I had planned for a CG that ultimately had to be removed.

ingthing

I wore too many hats. I tried to fill in all the smaller roles that I thought weren’t worth recruiting for, and as a result, I got incredibly overwhelmed with how much work I’d given myself, on top of leading the team and managing their schedules.

anonymous

It was really a struggle to be both the writer and artist, since many of the other components of the game rely on the script being completed (programming, music, sound effect insertion) but being the only artist meant I needed to dedicate early energy to designing the characters and their sprites too. Pushing back the writing meant further crunch was needed to get the rest of the game done ([especially] the roles of my teammates but also on the art side), so that’s really something to avoid in the future at all costs.

We also had some issues agreeing on character design choices which reflected a bigger challenge: differing communication styles = different expectations about what is useful feedback.

vanade

I badly let down an artist early on: in my eagerness to get a team formed early, I took on a member without properly vetting their past work to ensure it would be a good fit. Within a week it was very clear that they simply could not fulfill the brief as given, and because I didn’t do my due diligence at the start, I’d set them up to fail. We (amicably) parted ways, and I was able to hire someone to step into the gap, but it was a shameful error on my part and something I’ve learned from.

anonymous

It would be people not interested/ felt burdened just ghosting. You need to always check on your members, especially if they are being silent. Doing DM is the best, then talk it out. Usually, if they don’t reply 3 days max I just assume they drop out.

anonymous

One of the team members didn’t read the game design document properly, leading to a creative conflict. I figured you should really ask and not assume (that they’re reading things). Even though it’ll make you look dumb sometimes, you have to ask the obvious sometimes.

anonymous

Crunch towards the end of development time, especially in my first project as a director. For game jams, it’s hard not to crunch on the final week… but that doesn’t mean its pleasant for anyone involved.

madocallie

A lot of responses mentioned inexperience, team members not communicating or ghosting, miscommunication, and having a larger scope than they could manage.

What was one part that was harder than expected for you?

Kicking someone, who promised to deliver, off the team. Especially when they delivered well the last time we worked together. Even more so when you become friends through it. But as a team leader, it’s more important to make sure that everyone else’s contribution gets realized in a final releasable game jam submission.

anonymous

I tempered my expectations going in, so it was about as difficult as I expected. You need to maintain firm control over the project timeline and not let anything get out of hand. Despite having “finished” the game a week early, we were working right up until the deadline fixing things and adding quality of life features. A single mistake can have a ripple effect and completely derail the project timeline.

Kinjo Goldbar

Trying to time things to get done at the same time. At first, I tried having a very strict schedule, but learned that adding wiggle room is much better and easier on everyone.

TheChosenGiraffe

Learning the gist every other discipline outside of my own (like music, art) and trying to communicate my ideas in a way that make sense to the individual, especially when delivering feedback.

anonymous

Reassuring team members that their input was valuable and contributions were good for the game. The shorter turnaround times of the jam meant not much time could be spent polishing certain assets, and some team members had perfectionist mindsets that could slow production. It took a lot to keep morale high and adopt a ‘finished not perfect’ attitude.

anonymous

Managing communication between team members: I did not anticipate how much time and energy would be devoted to conflict resolution, helping establish boundaries, and facilitating dialogue. Tensions run high when working under a compressed timeline, and working with new collaborators, not everyone is necessarily going to mesh well. I learned early on that I couldn’t take my hands off the wheel and trust people to sort it out alone, and I spent at least as much time trying to resolve conflicts and diffuse tension as I did on assets relating more directly to the project.

anonymous

Everything with voice acting took longer. Recording sessions took FOREVER, and then scripting (implementing the voice lines, as well as expressions/positions) took the extra couple of days I’d budgeted at the end for overflowing.

anonymous

Managing Voice Actors. If you are someone new to this then I suggest finding someone to help you. You would end up failing them if you end up not using the recorded lines they made for you.

anonymous

I feel like the sense of inadequacy for the role can be a real challenge. Like you aren’t doing the rest of your team justice. It’s something you have to push through and encourage yourself by telling you that you’re doing a good job.

Brookiko

A few people also voiced frustration at trying to market their VNs during the jam. For this, all I have to say is to focus on the story you’re creating and share tidbits of that.

What was one part that was easier than expected for you?

Finishing before the deadline, and within the originally planned scope! An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure, and spending the month leading up to the jam in planning paid off enormously: by the time the jam started, everyone had a good understanding of the story we were coming together to create, and the timeline we each would have to create it in. Being flexible and having backup plans in place also helped a great deal, and acted as a good pressure-valve when things got to stressful: is it causing someone a nasty headache? Time for Plan B!

anonymous

If you’re with people that you feel confident in and have good references for them to work with, then the process can go by very smoothly.

Brookiko

Meeting all our deadlines for different parts of the game. Within preproduction and planning phases, we made a Gantt chart to mark tasks complete. This made it easy to visualise different tasks’ length and how they might overlap on different days.

anonymous

Coordinating a large team. A team of 31 (which we had for Spooktober) is not more difficult to manage if you have the right infrastructure in place. The five department leads (Art, VO, Audio, Narrative, and Programming) were great about facilitating communication, but I found myself more than capable of navigating through the whole team singlehandedly anyway.

Outlining expectations early was most helpful. Everyone knew who was responsible for what, the chains of command were very short and very clear, and everyone felt like they were a part of a cohesive team because everyone knew somewhat what the final product would involve.

anonymous

Communication is the easier part. Just don’t be shy and tell them what you want if it’s feasible or not. You are the leader and should be vocal about the instructions the team members need to do.

anonymous

The part the came out to be much easier than I could ever expect was actually dealing with other people! I’m not a very social person myself, but everyone was just so supportive, friendly and understanding that I could not have felt any more at home than I did. It was cathartic. Absolutely everyone in the team was a blast to work with it, and I do not regret a single second of it. I hope to keep working with them in the future and, one day, be as good and as talented as they all are!

Eriszsz

Quite a few people said that proper planning and direct communication saved them a lot of headaches during their game jams. Being as transparent and upfront with team members as you can will save a lot of time and frustration.

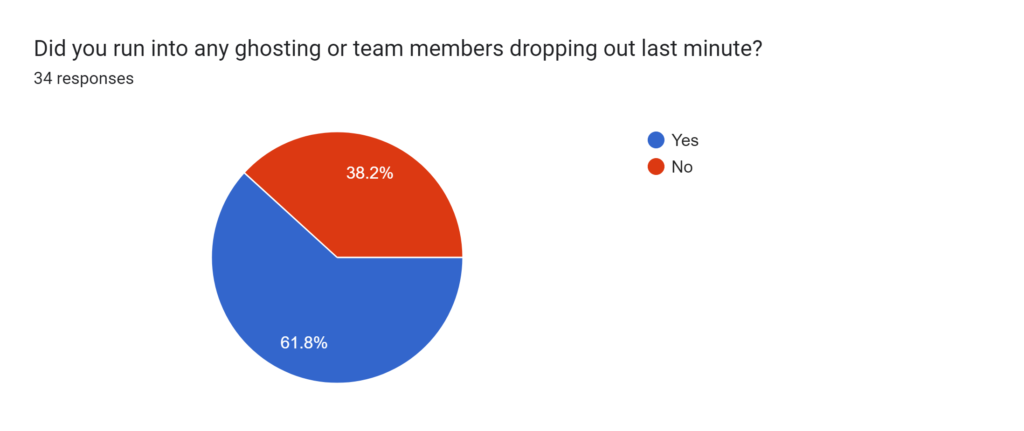

Did you run into any ghosting or team members dropping out last minute?

Over half of the participants said that yes, they did experience ghosting during their jam projects.

For those unaware, ghosting is when a person drops communication with you out of the blue and does not respond to any other messages for a period of time afterwards or forever. Members ghosting during game jams is sadly a common problem for a multitude of reasons- IRL issues; stress brought on from the work; miscommunication; unaware of team etiquette; etc.

To be clear, ghosting is never a good solution. If you find yourself needing to drop out of a game jam, you should inform the team lead as soon as you’re aware of it. If the workload given to you is too much, inform the team lead. Always try to work things out—if you ghost a team, you usually end up burning those bridges and being blacklisted by those people.

As a team lead, you should always consider the fact that someone on your team—even friends—may ghost you. Make backup plans incase work ends up being left on the table so you are still able to finish the game in time.

Was there anything that caused these members to drop out that you think could have been avoided?

You need to make sure they aren’t overloaded with work.

anonymous

Being honest about communication and workload. I always try to be as transparent as possible with how much work each person will have. Many accept willingly, but then realize its too much. They either drop out or ghost.

TheChosenGiraffe

Nah, everyone who dropped had minor roles in the team and had to leave due to IRL issues. Team structure was very flexible, with the art lead and I as the core parts of the team, having about 2-3 other people per project as major contributors that stayed consistent throughout, and then a few pitch hitters here and there who came in and gave assistance on a few assets.

anonymous

[I] should’ve started looking for replacement earlier tbh, the issue was that the person was replying all the time and promising to get stuff done ‘soon’ and ended up never doing it anonymous

Our main programmer had a weekend-long event planned in advance on the last weekend of the jam which they didn’t tell us until a couple of days before. They let us know they may not be as responsive then, then completely ghosted us (and still is mia). This could have been avoided had they told us about the event before the jam started, or at least a week or so before to give us time to find another programmer.

anonymous

A lot of the responses were either expressing that better communication would have probably solved the problem or said that it was out of their control.

What is your biggest regret from leading a team?

Thinking just calling the shots would be an easier job than doing the work.

PumpkinSpike

For my first one I lead, I wished I was more prepared which is why I now make sure to prep before a jam.

Brookiko

Being too stressed. I start worrying about how and when things will get done before a jam will even start. It’s important to be conscientious, but not to the point where the whole thing is just an unnecessary stressor. At times, I found my stress stressed others out so I learned to tone it down.

TheChosenGiraffe

[L]etting any part of the scope creep up on me – my one goal for these jams is to not burn out any of my team members or overwork them. It should be a fun challenge, not something to stress over. anonymous

[M]y hope was to have an enjoyable collaboration with new people, and to share a communal sense of pride in the finished work, but because some personalities were in conflict, it became a lot more stressful and a lot less fun for everyone involved. I’m still very proud of the finished work, but creating it wasn’t the fun, positive collaborative experience I hoped to cultivate. anonymous

I wish I’d gone with a slightly smaller game. 10k words isn’t too unreasonable, but 10 characters was way too many. Also voice acting, while fun, wasn’t something realistically viable in a month-long jam.

anonymous

Not being an effective communicator, not setting clear deadlines, not checking in on team members enough when it seemed like they might be struggling or not communicating back.

anonymous

Giving multiple roles to one person. If that person ends up quitting then the team is doomed unless you quickly find multiple people to fill in.

anonymous

What is something (positive/neutral, not negative) you learned from leading a team?

Keep your teams as small as reasonably possible. More people is more potential for things to go wrong, and if you don’t like interaction, more people to need daily/weekly check-ins.

PumpkinSpike

Learnt to communicate better and more precisely my ideas, as well and to stay in touch properly with all the team.

anonymous

It’s honestly an rewarding experience despite the fears and risks that can come into play. You learn a lot from people outside of your discipline and learn how to adapt to those who have different work routines to produce a great game. And, then you take the things you learn and put them forward to make another great game.

anonymous

Motivation is contagious. You have to keep a positive attitude and encourage your team to do the same. When you inspire your team, it shines in their work, and the positive energy cycles back to inspire you even more. And highly motivated people produce good work.

anonymous

To be okay with not a perfect product, since you can’t control everything. You have to make a priority list of the goals you want to hit. And each time I lead another team, I learn more how to prepare better for it.

anonymous

Leading a team in a jam context is very different from for a longer haul project; in this case I worked with two people from my main game’s team, but it functioned differently by virtue of the timeline being so short and the jam game itself being unpaid. I learned through this jam team that being flexible and/or open about the outcome of outsourced materials makes the jam experience much smoother! Thinking about assets in terms of the overall intent and effect for a jam game is more conducive to getting it all done compared to thinking about specific outcomes for each asset.

ingthing

I learned that I’m not exempt from allowing myself the same grace that I give my teammates. If I know I’m not going to be too hard on someone because I understand their and the jam limits, why should I be too hard on myself?

anonymous

Advance planning is of paramount importance, both in terms of the project’s scope and goals, but also in recruitment! Know who you are collaborating with, familiarize yourself with their previous work, and–especially if you haven’t worked together before!–make certain that everyone on the team understands everyone else’s boundaries. Get to know your collaborating artists and find out their expectations and needs going in: personality conflicts can’t always be predicted in advance, but clearly established boundaries and lines of communication can help mitigate how much stress they generate.

anonymous

Expectations about how to give feedback and how much feedback differ from person to person. Making concessions is important to keep your project moving along, and everyone should get to keep something so that there’s no resentment either.

vanade

wrapping up

I think this is the perfect response to end this article on:

People, at the end of the day, are good, and want to create good things with other people. If you find the right people, you will create something beautiful.

anonymous

Game jams should be—at least partially—about having fun and making something worth making. Game jams are a great time to experiment, to try new things, to meet new people, and a core element of creating things should be to have fun with it.

Let’s wrap up with some overall advice from myself and the other VN devs.

- Plan before the jam starts and well before you begin recruiting. Have an idea of what you want to make, or bounce ideas off of someone.

- Don’t bring on people without looking at their prior work and seeing if it’ll fit your vision.

- Keep your scope small and manageable. Don’t be afraid to trim it down.

- Plan for the unexpected. People having to drop, needing extra time playtesting, people not meeting deadlines, all of these can push back the deadlines.

- Communication is key. Be as transparent and upfront with people as possible.

- Check in on team members. Double check that their workload is doable for them and can be done in the timeframe.

- Ghosting might happen regardless of how open you are. Make backup plans before this happens.

- Don’t let stress get the best of you. You are the helm of the project.

Leading a team to make a game is a role in and of itself—it’s not some wonderful “idea guy” role, it’s an actual job. It takes a particular set of skills and is something you have to refine before you can get good at it.

Personally, I recommend working as part of someone else’s game jam team before diving into leadership. Learn from how others lead and how teams work before leading your own team, as it can be a very, very stressful thing.

Although I didn’t include them here, several comments I received mentioned how they had health-related problems arise while leading teams, including a couple that pinned the illnesses on the stress of leading said teams. While game jams are fun, these types of health issues are not to be taken lightly. Do not bite off more than you can chew. Take things one step at a time.

Thank you to everyone who helped me with this survey! I’ve included several links to users who responded up above with their quotes, so check out their works. If you’re looking for something else to read, maybe check out my article on if you should market your visual novel or not?

— Arimia